I remember being flooded with a grief so old

I remember the butcher’s shop on the Viminal Hill

My latest book is about the relationship between geography and power in the ancient Roman world, and most particularly about the visualisation of ideas about geography in the form of ‘geography products’*, at the interface between art and the geo-political environment.

As Rome broke its political bounds and headed towards empire the whole city became the centre of a larger world and the Roman worldview changed with it. The Roman state then needed to present to the Roman people an easily digestible narrative about its imperial ambitions and its imperial possessions, in a way that went beyond the fact that servitude, enslavement, and misery for many underpinned this expansion. There needed to be a publicly guided discourse centred around the smoothing out of difference, rather than its obliteration or elimination, and the presentation of very different lifeworlds in a familiar way. It marked a way of directing how change could be managed and a way of reimagining how the world might be and might work at the intersection between selection, presentation, knowledge, and insight. Reflection and communication sought then to create a communal sense of belonging.

By intensifying practices that stressed Roman individuality a process of drift was mitigated. Rome after all was not the first power to establish wide Mediterranean networks beyond home territory: indeed far from it. Rome’s external relationships were underpinned by strongly-articulated localised expressions which served to demarcate identity both internally and externally. Local and global practices interacting together played a significant and important role in Rome becoming what might awkwardly be called Mediterraneanised, as had previously and variously happened for others.

The creation of the Roman empire and its expansion almost inevitably led to a recalibration of spatial relationships between Rome and Italy and between Roman Italy and the rest of the known world as it was then. It is true to say that the detail is often in the small print of Roman culture, in its undercurrents. Geographical thinking shaped the forms of contemporary art then, even if only at the level of sub-genres, thus making my study a geography of art but not a study of geography in art, a political geography of the Roman world told through images, a strange spatial ontology layered onto Rome’s fixity in defined physical space. Extraterritoriality such as this can signify openness, freedom, imprisonment, or subjugation.

When writing the book there was an immediate realisation that the use of the umbrella categorisation of disparate ‘things’ as ‘geography products’ offered a number of potentially critical openings for looking at ancient Rome and its defining of place and space: that a new strand of critical conversation and dialogue could be started. Broadly such products included a slew of visual sources which acted as mnemonic triggers to spatial awareness and the definition can even be extended to encompass tastes, sounds, and smells which might have had the same effect. Written histories, geographic texts, ethnographic studies, poems, epigrams, plays, maps, drawn surveys, and inscriptions could also be geography products. Personifications, bodies and images of bodies could also on occasions be geography products or carry on them such information as to qualify in this respect: land, space, and place literally could be written on the body. I certainly believe that adopting this strategy of definition has allowed narratives, plots, structures, and themes in the evidence to emerge.

The history of Roman imperialism to some extent could be described as being a history of fragmentation and a history of exclusion. The city of Rome became a space where an attempt was made to create and present a kind of collective memory. If we can also then talk about moves towards inclusion our discussion has to be tempered with awareness of the constant undertow of cultural dislocation and alienation there. If environments can be said to inhabit us, then Rome became alive with peoples and products of the whole known world: it was not where you were but where you could be, through movement, transformation, becoming. The synaesthetic power involved must have been considerable, with light, music, texts, images, and architecture probably headily combining and proposing many routes through interzones into clear space, as images moved through time and mapped a geography of revelation and resolution. Low-frequency sightings rumbled up like suppressed memories of hauntological places, creating a topography of the human experience mediated by the viewer’s experiences and perspective. This was as much an exploration of ideas about place, a discourse on desires and the city form, as it was a continuation of architectural traditions.

Ideas relating to identity, alienation, assimilation, diaspora, and exile could be manifested and presented in the form of images in the Roman world without overt references to geography and origins, and yet inform viewers of just those very things through a mixture of lyricism and dialectics. These images were not simply part of a reflection of a separate or separated world of art: rather they were part of the passionate, rational, and dramatic aspects of everyday life at the time, sparking imaginations that were to be turned on the transformation of reality itself. Viewers were encouraged to discover within themselves desires for other, particular environments and places in order to make them seem real, to regenerate the nature of imagined experience under other skies. The tensions implicit in such strategies are obvious: the city became the total work of art, playing with the presentation of time, space, and place each in turn, then in tandem and combination. The solicitation of the city’s architecture and monuments was seductive and informative to those who were susceptible or open to suggestion. Information gleaned in this way reflected the absence of more practical means to orientate oneself in a changing and expanding world. The study and correlation of accepted snippets of geographical information obtained by cultural osmosis or sought out in a targetted manner on the city’s streets created new and what must sometimes have been very individual and idiosyncratic mental and emotional maps of both the existing cityscape and of distant imagined cities and places. These geographies framed Roman cultural practice. Representational and sometimes direct and sometimes almost abstract, intimate and monumental, systematised and impulsive, together these works did not break the rules of contemporary Roman art but they pushed the boundaries by signing up to all of them. If asked to say what they were about, I would say ‘everything’.

Although occasionally imprecise, these images conveying geographical information often in the form of architectural expression were often highly charged with emotionally evocative power and representing desires, control, events from the past, the present, and the future, rational extensions of religious experiences and myths. Imperial Rome ushered in a period of city planning seen as a means of knowledge exchange. Parts of the city could have corresponded to the feelings usually experienced by chance, but here managed or even manipulated. One could leave the realm of direct experience for that of representation and presentation. The passivity of the old, pre-imperial Rome needed to be reconstituted in some respects by a collective project explicitly concerned with confronting every aspect of the audience’s lived experiences, by drawing attention to the contrast between what contemporary life was actually like and what it could be. Rome could only find its poetry in the present, if informed by the past.

Roman ideas and concepts about geographic space, about topography, about landscape, about foreign peoples, and about barbarians were developed, one might even say workshopped, in the theatrical sense, through a process of almost trial and error in terms of creating and presenting a coherent series of geography products which utilised words and images to telescope distance and space and to create maps of the body and maps of the mind. The recurrence of these intercalations between political ideology and images was not always simply a repetition of the same thing. There were undoubtedly significant shifts and developments in the way that these encounters were negotiated and whether a meaningful historical trajectory can be discerned in the multiplicity of meanings presented and entangled in the process.

Especially dramatic and portentous was how empowerment with geographic knowledge, when it took place, found expression in new aesthetic practices. Cultural power here was in many ways analogous to economic power. This was not to deny the inherent tension here, that the full pursuit of economic capital was usually incompatible with the full pursuit of cultural capital. Indeed, the process became altogether saturated with aesthetic discourses at the expense of other interpretations. A genealogy of such geographical images was not seeking to provide a continuous history, a seamless narrative, but rather to focus on certain eruptions, breaks, and displacements of the cultural field. It stressed heterogeneities and specificities. Genealogies focused on struggle and competition and were interested less in the narrative of events than in patterns and structures.

Everything in the geographical field must have acted like a citation, embedded discourse, mention rather than use. The false symmetries of good sense reflected techniques of compression and collage, myths of abjection and omnipotence. Homesickness was presented here as a pathology and became a conduit through which a world could emerge. Any attempt to constitute the images as settled carriers of meaning might have run aground on their incompleteness and inconsistency.

In the end almost everything that had directly lived under the Roman system moved into a representation, caught between everywhere and nowhere, geographical images embodying a very particular sensibility and representing a site or locus of deluded aspirations, and yet at the same time probably occasionally freeing the imagination and shackled ambition. All of this emerged in tandem with the defining motifs: consumption, art, the scrambling of linearity, the debasing of perceived truths or grand narratives, the collapse of representation into reality: tensions born of such developments were engaged with and played out in various ways. The ideology lay in its practice, in its ability to pleasure, surprise, transgress, inspire, question and imagine, a mode of critique rather than a definite answer or solution. It confronted, challenged, and gave vent to a message that was both resonant and ambiguous, and it provided a space or spaces to reflect upon or explore the social tensions contained within it. It helped collapse the distinction between here and there and in many ways sought instinct, passion, caprice, and violence. Such images demonstrated a conflict between feelings of being rooted and rootless, belonging and not belonging, place and displacement.

Compassionate scrutiny probably would have revealed the moral complexity of many geographical images, a desire to be fully part of the world mediated by images of oscillation and unsettledness and shadows. Revelation would have helped shatter the sense of continual change, initiating the reuse of images to allow the past to exist in the perennial present. No longer were lost or marginal cultural resources recovered and reimagined: they existed concurrently to be collated, imitated, decontextualised, and disarmed. The differences that had always been contested merged or conflated, and point and purpose hardened as cultural forms evolved away from their initial stimulus. Cultural changes enabled competing sites of attention to operate contemporaneously and probably sometimes competitively too, continuing to provide a means of agency and a platform, even as its cultural traces were archived, appropriated, and often historicised, as was so much of Rome’s cultural output.

A process of critical engagement must have been required on the viewer’s part though, as these images must sometimes have appeared to be contradictory and formative, implicit and explicit, liberatory and reactionary. Meanings were projected but also cultivated from within, shaping the dialogues that ensued as cultural spaces were opened up. The exploration of sexual, psychological, and delinquent extremes was surely a bi-product of the viewing of such images by certain viewers.

Taken together, the collective assemblage of Roman geography products and geographical images were like a series of return journeys which could not be judged on output alone. There was so much more hidden, suggested, left to the imagination. The mystery was left caged. It remained an exception to the rule. Moments of viewing must have helped provide insight into life as a series of potentially random journeys that one might take or might imagine oneself taking, showing some viewers some of the possibilities.

The Romans had many ways to manage geographical information, not only by preparing texts of one sort or another and by literally inscribing themselves on the land of others, and had many scientific ways of handling geographical data. The surveyors’ groma, the cadastral plot, the drawn or inscribed ground-plan of a building, the city plan, the travel itinerary. These were things to help order, understand, and control space and place. But in order to conceptualise geographical knowledge and information art needed to be employed to spark the imagination, to suggest connections, to scare, to bewilder, or even to reassure.

These images had purpose, the images were maps of a kind. The great power of illusion, the often unspoken dynamics of society or community, and the excitement and thrill of pursuing empire and expansion all helped shape the people of Rome. The actual and emotional geography of the place in which they lived were intertwined, presented in a way that focused not so much on specific events but rather on subtexts, atmospheres, and perceptions. Though argued in the book not to have been direct, the message was nevertheless clear and present in the architecture of every image discussed and dissected, and in the sounds, the gestures, and the representations on which viewers were asked to turn their attention.

The sociological typology of these images was turned into something more strange and satisfying through the visionary dimension of the scene-setting and by context. The images described distant locations in an exuberant way that foregrounded knowledge and its transmission over experience. They also highlighted and encapsulated rather than denied the ambivalence many people would have felt about their city being part of a larger whole that they themselves had no direct experience of. They were viewing something that aimed to replace their own personal experience with a mediated narrative, hovering between projection and self-recognition, with events happening off stage and in their peripheral vision. This allowed the ordinary citizen with no experience of foreign travel to imagine the power plays behind conquest, violence, and the creation of empire, and to explore those relationships from a place of relative calm and ease. Certain tropes were deployed to a knowing audience, beating familiar pathways, both subverting and not diminishing expectations, creating reciprocity between the viewer and the presenter of the image. Each knew what these signifiers denoted: the process could be recuperative. These circumstantial geographies represented substance, not truth, and tapped in to contemporary desires. This cultural obsession with the idea of place permeated not only Rome’s political and ideological life but its religious life too, certainly up to and including the role of place in the mythology of Christianity, and had its origins in the Roman elite’s over-riding interest in ancestral connections to specific locales.

Rome and its citizens had slipped inexorably from dreams and expectations into an age of greatness, conjuring vivid, concrete images from the quotidian dullness of city life. The complexity and constraint of formal presentation nevertheless was a powerful manifestation of Roman state power, constantly confronting notions of difference and belonging in both a literal and a figurative set of journeys mediated by images.

There is a vast difference between the level and detail of geographical knowledge required to inform political and strategic intelligence decisions and simple background knowledge intended merely to inform those who need to be able to cope with the certainty of uncertainty in a shifting, unpredictable world. The latter was part of a broader suite of strategies required to acclimatise Rome’s citizens and other inhabitants there to the ever-changing nature of what it was to be Roman when the mother city was but a centre rather than simply its own enclosed world. Rome’s success was very much reliant on its ability to integrate and absorb exogenous elements into its host body, be they territories, peoples, cults and religions, and indeed cultural practices. This assimilation was, of course, not without its limits and exceptions, and more often than not achieved by force of arms rather than just by force of will. The spilling of blood could be regenerative for the Roman state in the same way that religious sacrifice underwrote individual piety. Violence was such a deeply entrenched threat in this world that it permeated and infected all human interactions. Trauma was not just an individual event: it was a psychosomatic experience on a social scale. Comparing a society or country to a body made an authoritarian or reactionary ordering of the world seem inevitable, somehow immutable, but the Romans could also liken the body to society, the body to a temple, to a city, to a fortress and so on.

Rather, this self-enclosed aesthetic system elided geography with anthropology, this unity in being of the personal and the social at its peak made sensate in the form of didactic images. But the viewing audience was not a blank canvas: the hyper-politicised urban plebs of Republican and early imperial Rome were anything but, even if their encounters with presented geographic images were intermittent and evanescent. Such images as an assemblage were united more by the myths that they intrinsically connoted and the environment and contexts within which they were framed than by the aesthetic or formal qualities they outwardly displayed. Taken together, it can be suggested that they did not have the specificity and tautness of a true series from which certain aesthetic conclusions or imperatives could be drawn. Rather, they served as a useful coded expression for a whole array of different messages and practices that existed as an extended and multifarious group with partial resemblances and differences, but not sharing any core aesthetic messages that made them one. The series, if considered as a single artistic project, approximated a kind of rapture by setting up a fluid interplay of visual and textual refrains, framing and contextualising existing archival images elsewhere in the city, creating a continuous frame of action and reactivation across the group.

Time and discourse at Rome were not only understood spatially but were mobilised in imaginative ways. The issue at stake was not simply one of iconography. Viewers would have been caught up in the very flux of psychogeography, interiorising the layout of the city, practiced in each of its pivots and sites of junction, digesting every single point of entry and exit. Such navigations would have connected distant moments and far-apart places by absorbing and connecting visual spaces. Narratives would have risen, built, unravelled, and dissipated, revealing potential sites of opening, an elsewhere that was nowhere. An obsession with searching and finding hints of distant lands and peoples would have both revealed and covered a fear of being lost. Presentation of a series might have aimed to corrode the opposition between mobility-immobility, inside-outside, private-public, and dwelling-travel, with architecture in Rome being a map of both dwelling and travelling.

Geographic images seem to have had a mirroring effect, the views of the city of Rome and vistas of foreign lands offered back to the urban audience for viewing. The effect of this must have been cumulative. Whichever path was followed there were different points at which fragments came together narratively. By making tours and detours, turns and returns, the viewer opened up on different vistas of the production of space. Spatio-visual arts created a bond between architecture, travel culture in all its forms, the history of visual art and its well-established tropes, and memory and map-making in its broadest, non-literal, meaning.

What was produced was a mixture of utopias, centred on imperial harmony, and dystopias, relating to conquest and enslavement. The drive to possession and domination created an erotics of knowledge, a spatial curiosity. The geographies of space and the body were combined in this age of exploration and empire. Art is often a powerful way to overcome our limits: limits in both time and space, limits of the mind itself, and limits of perception and capability.

I remember how even the cars in Rome looked ancient

I remember how all that was solid melted into air

* I have adopted the term ‘geography product’ from its use by Katja Pilhuj in her 2019 book Women and Geography On the Early Modern English Stage.

Iain Ferris is an independent academic researcher and a former field archaeologist who has published three archaeological excavation monographs and ten books, the most recent of which, Visions of the Roman North: Art and Identity in Northern Roman Britain, was published by Archaeopress in 2021.

A Map of the Body, a Map of the Mind: Visualising Geographical Knowledge in the Roman World by Iain Ferris

This study considers the relationship between geography and power in the Roman world, most particularly the visualisation of geographical knowledge in myriad forms of geography products: geographical treatises, histories, poems, personifications, landscape representations, images of barbarian peoples, maps, itineraries, and imported foodstuffs.

Forthcoming (Spring/Summer 2024)

ISBN 9781803277813 | Paperback: £45.00

Pre-order at archaeopress.com and save 25%: Use voucher code 781325

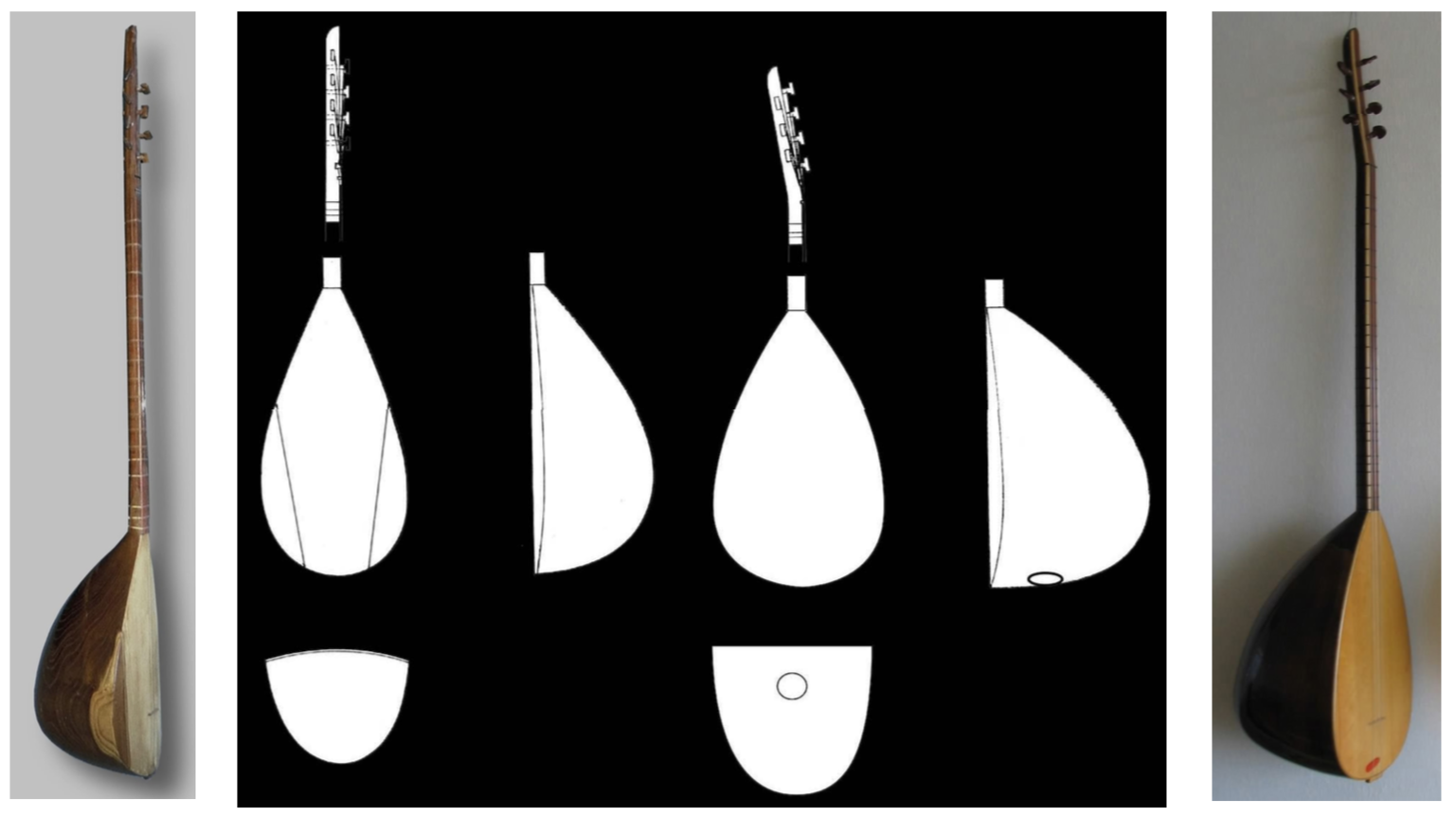

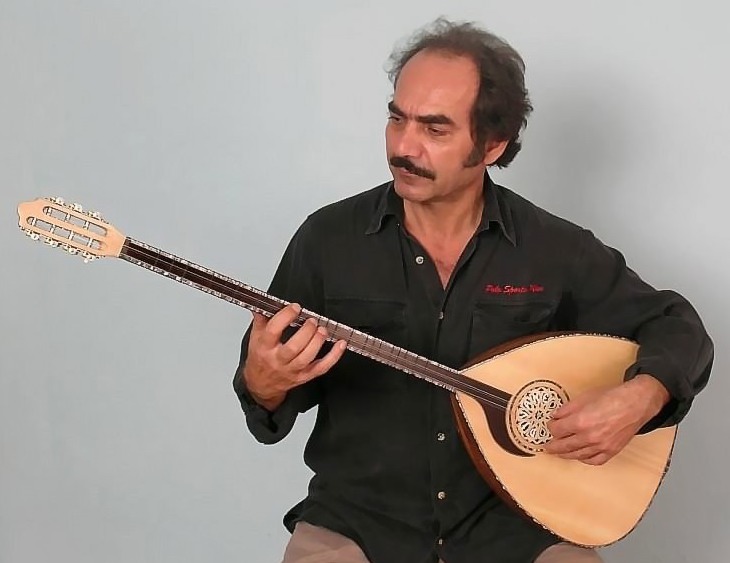

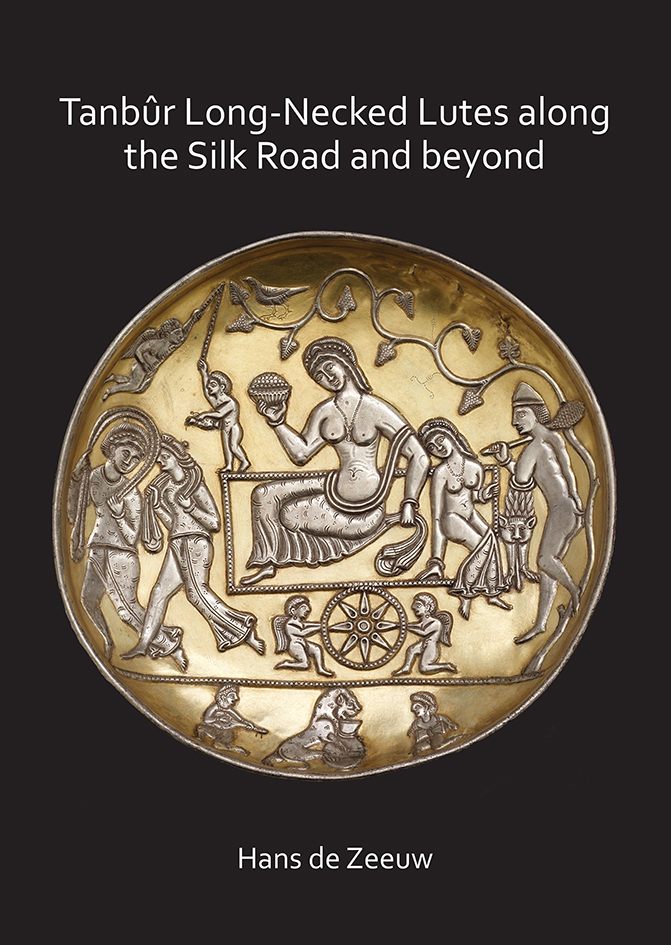

Sincerest thanks to Hans De Zeeuw for providing this article for the Archaeopress Blog.

Sincerest thanks to Hans De Zeeuw for providing this article for the Archaeopress Blog.

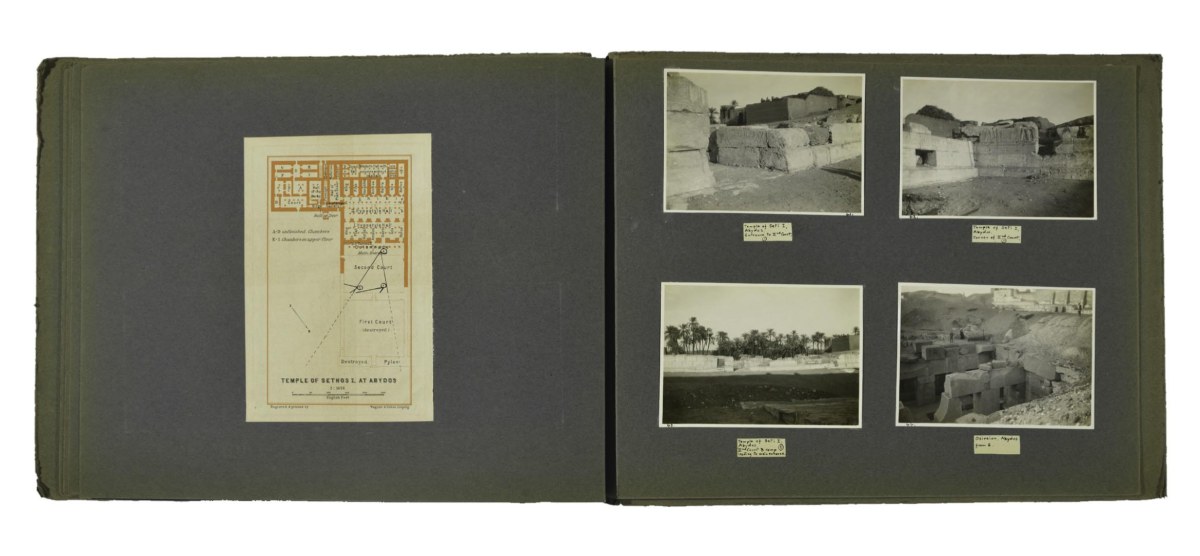

Ceramiche vicinorientali della Collezione Popolani by Stefano Anastasio and Lucia Botarelli. Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, 2016.

Ceramiche vicinorientali della Collezione Popolani by Stefano Anastasio and Lucia Botarelli. Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, 2016. Archeologia a Firenze: Città e Territorio Atti del Workshop. Firenze, 12-13 Aprile 2013 edited by Valeria d’Aquino, Guido Guarducci, Silvia Nencetti and Stefano Valentini. Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, 2015.

Archeologia a Firenze: Città e Territorio Atti del Workshop. Firenze, 12-13 Aprile 2013 edited by Valeria d’Aquino, Guido Guarducci, Silvia Nencetti and Stefano Valentini. Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, 2015.