The Old Kingdom of Egypt (Dynasties 4–6, c. 2600–2180 BC) is famous as the period that saw the building of the largest Egyptian pyramids. Generally, it has been accepted that only humble remains of copper alloy tools are preserved from this era. What might be more surprising, is that there has been little analytical work of archaeometallurgy on the preserved metal objects from the Old Kingdom. My name is Martin Odler; I am working at the Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague. Last November, Archaeopress published my book Old Kingdom Copper Tools and Model Tools, aiming to update the research on the metal tools of the pyramid builders and other craftsmen during the Old Kingdom.

My research was initiated by one of the largest Old Kingdom finds of copper alloy model tools in the tombs of the sons of Vizier Qar at Abusir South by a team from the Czech Institute of Egyptology, led by Miroslav Bárta, in early 2000s. The tools were from the Sixth Dynasty, reign of Pepy II, and altogether there were about 3 kilograms of copper found in the burial chambers. Copper tools became the topic of my M.A. thesis in 2009. After its defence, I received a grant from the Grant Agency of Charles University to study unpublished collections of copper alloy objects in the European museums and in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The monograph is a result of these research visits and also of the processing of the finds of copper alloy objects from Czech excavations at Abusir.

I have collected the textual, iconographic and palaeographic evidence. The evidence available to modern archaeologists is largely determined by preselection by the past culture, by conscious and unconscious rules that were applied to the creation and production of the sources. Everyone is aware of that, but in the case of the Old Kingdom, we have data that shows how much is missing from the evidence. Old Kingdom evidence shows in great detail the extent to which the range of artefacts available for study by archaeology today is influenced or even biased by a selection made by the past culture. Had it not been for the custom of depositing copper model tools in the burial equipment (and in the richest assemblages, there are altogether more than a thousand tools preserved), we would have almost nothing preserved from metal tools used in the era. Iconographic sources indicate the use of other metal artefacts that were not even fragmentarily preserved from the Old Kingdom (such as metal blades of weapons). Scattered finds from Old Kingdom settlements provide artefacts which were included neither in the burial equipment (or very rarely) nor in the iconography (e.g. needles). Harpoons and fish-hooks have their firm place in Old Kingdom iconography, yet their specimens in the Old Kingdom material culture are rather rare.

Furthermore, I have provided in the book updated definitions of tool classes and tool kits, together with the context of their use. They can be divided into artisan tool kit (comprising chisels, adzes, axes, saws and drills), cosmetic tool kit (razors, mirrors, tweezers, hair curlers, kohl-sticks and cosmetic spatulas), weaving tool kit (needles, awls and pins), leather-working tool kit (leather-cutting knife), hunting weapons and tools for food procurement (fish-hooks, harpoons, knives), and weapons as a separate category of metal blades (battle axes, arrowheads, spearheads, and daggers).

Besides rare specimens of full-size tools, scattered in the museum collections world-wide, the largest corpora of the material have been preserved in the form of model tools in the burial equipment of the Old Kingdom elite and were most probably symbols of their power to commission and fund craftwork. Metal tools occurred already in the Pre-dynastic Period, in the graves belonging probably to craftsmen and also in the rich graves of the supposed elite. It is hard to believe that kings and high officials spent their time in craftwork; already then, the tools were most likely to have been symbolical representation of the elite households, with craftsmen present in the households (and in the subsidiary graves) to wield those tools.

I should dispel one of the most common misunderstandings. You may have read in many popular and semi-popular works that Old Kingdom Egyptians knew and used only tools made of pure copper. This is simply not true; they were using arsenical copper as the main practical alloy, typical for the whole Ancient Near East in the Early Bronze Age. For Egypt, this fact was proven already in 1976, in an article “Near eastern alloying and some textual evidence for the early use of arsenical copper” by E. R. Eaton and Hugh McKerrell. Already, in the Early Dynastic Period, Egyptians certainly knew bronze as the oldest securely-dated bronze objects, spouted jar and wash basin, have been found in the tomb of King Khasekhemwy, built and furnished at the end of Second Dynasty. To know more, we need to analyse more objects from secure archaeological contexts.

The long-standing division in the Egyptological literature between full-size tools and model tools is questioned. One of the most important arguments is that the traces of tools on objects are actually very close to the size of some bigger so-called “model tools”. The typology alone and use of the preserved textual and iconographic sources are not sufficient for the correct understanding of Old Kingdom material culture. Typological studies can be enriched by the use of morphometry, further vital knowledge can be provided by the archaeometallurgical study of the objects. Statistical studies of Old Kingdom material culture are only just beginning, with an exception of Old Kingdom pottery. Ceramic studies have thrived in recent decades and more Egyptologists than ever realize the importance of pottery for the reconstruction of the site histories.

The volume is completed by co-authored case studies and Archaeopress agreed to post all four on academia.edu and Research Gate. The first one is a detailed archaeometallurgical study of selected Old Kingdom artefacts in the collection of the Egyptian Museum of Leipzig University in Germany (as a brief aside, the research was approved by the curator of the collection, Dietrich Raue, whose team recently discovered a Late Period colossus in the temple of Heliopolis). The research was in this case led by my colleague Jiří Kmošek, a specialist on Prehistoric metallurgy. One of the most interesting findings of the project is that Old Kingdom Egyptians did not rely on alloying properties of arsenic, but instead annealed and hammered the objects to create the desired shape and hardness of the object. Research goes on, we have submitted the samples for neutron activation and lead isotope analyses, and you can look forward to news about the origin of the alloys used for the production of Old Kingdom objects.

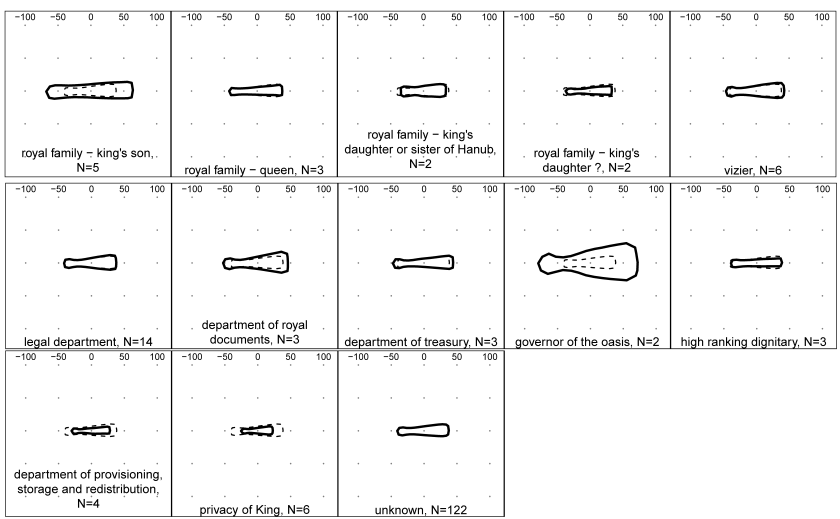

The second case study is the first application ever of a method of geometric morphometry on a corpus of ancient Egyptian copper tools, in this case Old Kingdom adze blades. We have analysed the assemblage with a mathematician Ján Dupej. Morphometry proved my suspicion, already expressed elsewhere, that the size of the model tools is somehow connected to the specific parts of the sites and social status of the buried persons. The bigger the models are, the higher the status of the person. However, this rule is sometimes broken by less affluent officials and I think that those bigger models were probably “royal” gifts. Although uninscribed, they might have been perceived as status objects by the Old Kingdom Egyptians.

Two remaining case studies were written by my colleagues from the Czech Institute of Egyptology, Lucie Jirásková, about the stone vessel finds associated with copper model tools, and Katarína Arias Kytnarová, on the ceramic vessels in the same contexts. Old Kingdom tombs are frequently dated on the basis of iconographic and textual evidence. Yet the tomb decoration must have been planned and executed well in advance. The objects associated with burials might be in fact closer to the actual dating of the burials themselves, and this dating does not always match the tomb decoration. But this is also a task of future research, at the Czech concession in Abusir and elsewhere on Old Kingdom sites in Egypt.

My book is only one of the steps leading to better knowledge of ancient Egyptian material culture. Already when submitting the final manuscript, I knew that the contents could not be called complete. In spring 2016, we excavated anonymous tomb AC 31 at Central/Royal Abusir, a tomb with rich remains of original Fifth Dynasty burial equipment, including copper model tools. The tomb provided us with incredibly detailed information on the late Fifth Dynasty burials of the elite, and we now know that it is one of the most important Czech discoveries at Abusir.

There are also some open questions, regarding which my book could be helpful for future research. If you would like to produce for yourself your own Old Kingdom artisan tool kit and do experimental work with it, the drawings of the tools are published. But, please, document it. Also the tool traces on the Old Kingdom objects need to be gathered in a more systematic way. My current research is focussed on the archaeological evaluation of the archaeometallurgical analyses of objects from the Egyptian Museum of Leipzig University (not only from the Old Kingdom). The first phase of the research was presented last year at 41st International Symposium on Archaeometry in Kalamata (Greece) and our poster received honourable mention from the Society for Archaeological Sciences in the R.E. Taylor Student Poster Award. Another project focused on the ancient Egyptian objects from the documented archaeological contexts in the collection of Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, datable from the First Dynasty to the Second Intermediate Period. The results of both projects will be published this year and hopefully I will write about them more in a future post on the Archaeopress Blog.

Martin Odler’s book, Old Kingdom Copper Tools and Model Tools, Archaeopress Egyptology 14, 2016, is available now in paperback (£45.00) or as a PDF eBook (£16 + VAT if applicable). The paperback edition will be available at the specially reduced price of £36 until 30/04/2017 at www.archaeopress.com.

Martin Odler’s book, Old Kingdom Copper Tools and Model Tools, Archaeopress Egyptology 14, 2016, is available now in paperback (£45.00) or as a PDF eBook (£16 + VAT if applicable). The paperback edition will be available at the specially reduced price of £36 until 30/04/2017 at www.archaeopress.com.

Praise for Old Kingdom Copper Tools and Model Tools:

“In short: the authors have succeeded in presenting a reference and standard work, in which no one who is concerned with this period and this material should pass by; a work that will always be consulted with pleasure and joy.” – Robert Kuhn, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (KunstbuchAnzeiger.de) (Translated from the German)

Sincerest thanks to Martin Odler for submitting this article for the Archaeopress Blog. If you would like to submit something for consideration to be published on the blog please contact Patrick Harris (patrick@archaeopress.com). Articles on all aspects of archaeology will be considered. They should be approximately 2,000 words accompanied by up to five images.