Commercially driven copies are conventionally considered to lack relevance to heritage because they are of recent origin and lack heritage values. But for others, including us, heritage should be valued in relation, not to its origin, but to its function in society. In the past, research on cultural heritage has centered on material things which can be catalogued, listed, conserved. In the last decade, heritage has been redefined as an area that is concerned primarily with people. Heritage is now theorized as a range of cultural practices in which people invest meanings to things and ascribe values to them (Smith, 2006; Filippucci, 2009). Heritage is a process which creates new meanings and values, and the cultural meanings of heritage are validated through linkage to the past (Smith 2006). To date, research on the interactions of people, material things and relevant cultural processes is frustratingly scarce (Wells 2015).

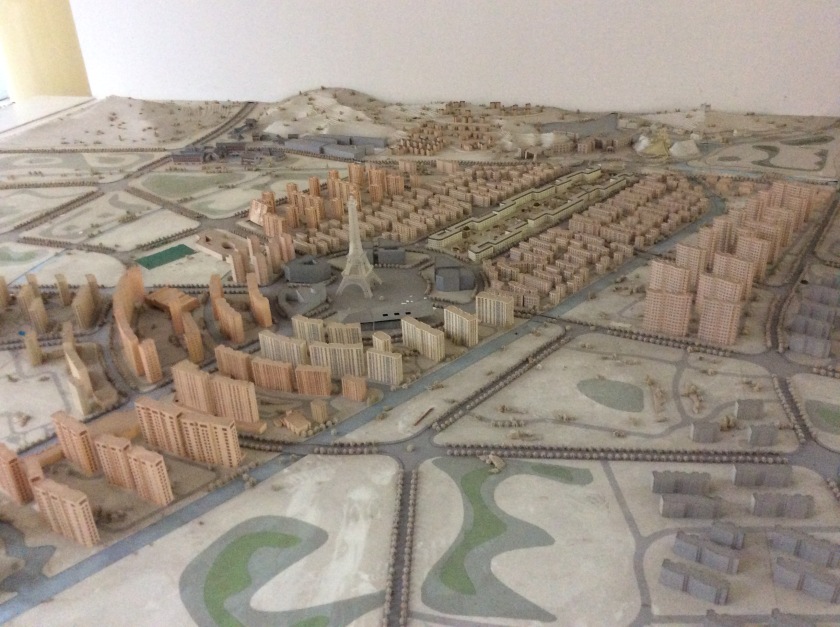

These issues can be illuminated further by the case of Tianducheng (Sky City), a simulated heritage site in Hangzhou, China. The city is a large suburb, which is designed to incorporate a selection of very prominent architectural heritage features from France including a 1:3 scale but nevertheless imposing copy of the Eiffel Tower in Paris (fig. 1). It is one of many suburbs in China that resemble far-away places and include copies of foreign historical landmarks, reflecting Chinese imaginations of the Western lifestyle (Boskar 2013, Piazzoni 2018). These suburbs are commodities that originated in a specific economic and cultural framework of contemporary China. As such, Tianducheng is part of the cultural heritage of early 21st century China. But questions are also raised about the relationship to the original heritage sites in France which Tianducheng evokes.

Arguably, more important than age is the experience of pastness which has been defined by Holtorf as the quality for a given object to be ‘of the past’. The presence of pastness is not related to age but specific to a particular perception situated in a given social and cultural context (Holtorf 2017a: 500). The Eiffel Tower in Hangzhou may not fool anybody about its recent age. But it plays on pastness insofar as it matches exactly people’s expectations of French 19th century architecture and the history that connects that architecture with the present-day city of Paris. We can therefore, in this case, speak of simulated heritage. It simulates the pastness of Paris’ heritage in another city, Hangzhou in China. We suggest that a strict distinction between simulated and non-simulated cultural heritage is not particularly helpful in any attempt at understanding either; instead we should be looking at what they share with each other (see also Holtorf 2017b).

Tianducheng was initiated by the real-estate company Guangsha Group which started this enormous project in 2001. It was a pioneering project back then, for this corporation wanted to build a self-sustained satellite city around Hangzhou and contended to lead the urbanization process in China. On the webpage of this property, it advertises itself as “taking France culture as its city culture” while “setting ‘business, tourism, residency and education’ as its pillar industry in this city” (http://www.guangsha.com/index.php/newsinfor/23/3682). The Eiffel Tower and the nearby park were finished before the apartment buildings were sold. They present a clear image of French culture to attract people to buy properties and settle down in Tianducheng (figure 2).

Interestingly, the construction of both the original and the Chinese Eiffel Towers were hotly debated. Opened in 1889, the French tower was widely criticized by the cultural elite at the time but became a huge popular success. Intended to be dismantled after 20 years, the 324m tall tower became a valuable asset for the city and has not only been maintained until the present day but also copied several times at other locations in the world (Wikipedia n.d.). Built in 2007, the 108m tall Chinese Eiffel Tower went through a similar controversy. On 20 November 2010, Guangsha Group started to dismantle the tower without notice, which caused a backlash among residents (Chen 2010). Many residents called the media to report what was going on and hung protest banners on the tower. After negotiation, the company decided to cease dismantling and returned the tower to its original condition.

Arguably, Tianducheng fulfills some of the same functions of heritage in Hangzhou as the original sites fulfill in France, in relation to place-making, for example. According to Laurajane Smith (2006: 79), place is “not only a space where meaningful experiences occur, but is also where meanings are contested and negotiated.” Indeed, place “provides a profound centre of human existence to which people have deep emotional and psychological ties and is part of the complex processes through which individuals and groups define themselves” (Convery et al. 2012, p. 1). People’s sources of meaning and experience as well as their environments all contribute to place-making (Harvey 2001). In the case of Tianducheng, as of course with the French original, local residents construct their sense of place from the iconic tower, its magnificent view during daytime and the light show on display at night, as well as from various leisurely activities around the tower. At daytime, it is relatively quiet. When the night curtain falls, it is lively, and can indeed be difficult to find parking spaces. Many people come here to enjoy square dancing with friends, to visit restaurants, and enjoy the tower light show. What is most important is not the question of whether or not the architecture has been copied, but how each site contributes to the local residents’ lives and their sense of place.

We spoke to some of the local population living in Tianducheng. More and more people choose to settle there, and the majority of them seem to enjoy the place very much. A shopper we spoke with stated that “of course we know we are not in Paris, everybody knows that. But we still enjoy the view and relaxing atmosphere.” On a web forum of local residents, many others expressed their appreciation of the site, too. There are also visitors going there, taking photos to “pretend” that they are in Paris and subsequently posting them on WeChat moments (similar to Twitter). This applies in particular to wedding pictures. The tower serves as a widely known symbol and icon. When people want to meet somewhere or when they want to locate a certain place, they tend to use the tower as a reference point. One of our interviewees is a member of the local Yixing jogging group. Among other activities, the group meets every morning underneath the tower to start a jog around the city. Ma Gangwei, the interviewee, said, “I like it here. But I don’t have any particular thoughts about this France thing. …I’ve never been to France. I don’t know what it is like to live in Paris. But I like the surroundings here. It might not have much to do with the architectural style. It’s about the park, the mountain, the environment here.”

Tianducheng is both French and Chinese. Some of the shops in the associated commercial district express an emerging hybrid heritage. One restaurant is called “Champs Elysees Noodle Restaurant”, but it serves local food, a kind of noodles from a city in the Zhejaing province (figure 3). Whereas the simulated Eiffel Tower may represent the power of cultural globalization, the local businesses and their customers appropriate the attractiveness of the iconic structure to enhance the practice of their own traditions. In that sense, we may see in Tianducheng a case where “global forces create conditions for local traditions to survive” (Reisinger 2013: 41). Somewhat ironically but hardly surprising, there are likely some Chinese restaurants in walking distance from the French tower, too. Many seemingly clear distinctions between the French and the Chinese versions of “Paris” and the “Eiffel Tower” thus fade away on closer inspection. What emerges is a common heritage value of the Eiffel Tower materialized on opposite sides of our planet in hybrid forms.

Places like Tianducheng simulate heritage, but at the same time they provide real heritage value in society and should therefore not be dismissed. In cases such as this, we may see some glimpses of a future of heritage that contradicts and replaces familiar concepts of cultural heritage bound to place and time. Tianducheng challenges us to think carefully about the possible character of future pasts and their benefits in society (Holtorf 2017b). It raises some profound questions: will there soon be many more suburbs around the world that simulate the past of other places? Should heritage experts and historians welcome them in the same manner as local communities do, appreciating their qualities? Does China lead the way towards the future of the past?

References

Boskar, Bianca (2013) Original Copies. Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China. Hongkong: University of Hongkong Press and Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Chen, Xiang (2010) The landmark of Tiandu city is gone. Morning Express.November 22nd, 2010, A0003

Convery, I., Corsane, G., & Davis, P. (Eds.). (2014). Introduction: Making Sense of Place. In Convery, I., Corsane, G., & Davis, P. (Eds.). Making sense of place: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

Filippucci, P (2009) Heritage and Methodology: A view from social anthropology. In Sørensen, M. L. S., & Carman, J. (Eds.). Heritage studies: Methods and approaches. London and New York: Routledge.

Harvey, Penelope. (2001) Landscape and Commerce: Creating Contexts for the Exercise of Power. In Bender, Barbara, Winter, Margot. (Eds). Contested Landscapes: Movement, Exile and Place. Oxford: Berg.

Holtorf, Cornelius (2017a) Perceiving the Past: From Age Value to Pastness. International Journal of Cultural Property 24 (4), 497-515.

Holtorf, Cornelius (2017b) “Changing Concepts of Temporality in Cultural Heritage and Themed Environments.” In: F. Carlà-Uhink, F. Freitag, S. Mittermeier and A. Schwarz (eds) Time and Temporality in Theme Parks, pp. 115-130. Hannover: Wehrhahn.

Piazzoni, Maria Francesca (2018) The Real Fake. Authenticity and the Production of Space. New York: Fordham.

Reisinger, Yvette (2013) Reflections on globalisation and cultural tourism. In: M. Smith and G. Richards (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Tourism, pp. 40-46. London and New York Routledge.

Smith, Laurajane (2006) Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

Wells, Jeremy C. (2015). Making a Case for Historic Place Conservation Based on People’s Values. Forum Journal, 29 (3), 44-62.

Wikipedia (n.d.) Eiffel Tower. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eiffel_Tower (accessed 18 Nov 2018)

Sincerest thanks to Cornelius Holtorf, Qingkai Ma, Xian Chen, and Yu Zhang for providing this article for the Archaeopress Blog.

Sincerest thanks to Cornelius Holtorf, Qingkai Ma, Xian Chen, and Yu Zhang for providing this article for the Archaeopress Blog.

Further reading available from Archaeopress:

The Archaeology of Time Travel: Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century edited by Bodil Petersson and Cornelius Holtorf

Paperback ISBN 9781784915001 (£38)

eBook available as a FREE download: Download here.

Search the Past – Find the Present: Qualities of archaeology and heritage in contemporary society by Cornelius Holtorf

eBook available as a FREE download: Download here.

Contribute to the Archaeopress Blog: Send your proposal for a short article (1,000-2,000 words plus 4-8 illustrations) to Patrick Harris at patrick@archaeopress.com